Merriam’s Wild Turkey Hunting Tips

The Merriam’s wild turkey is a mountain nomad that will test your legs, your lungs, and your will to succeed. These white-tipped wanderers live in some of the most beautiful and brutal country in America – vast ponderosa pine forests, windswept meadows, and high-altitude terrain that separates the weekend warriors from the serious hunters. If you want to hunt birds that travel miles in a day, gobble with a wispy mountain yodel, and inhabit country where a single wrong step could end your hunt permanently, then Merriam’s turkeys are your ticket to the real deal.

Biology and Physical Characteristics

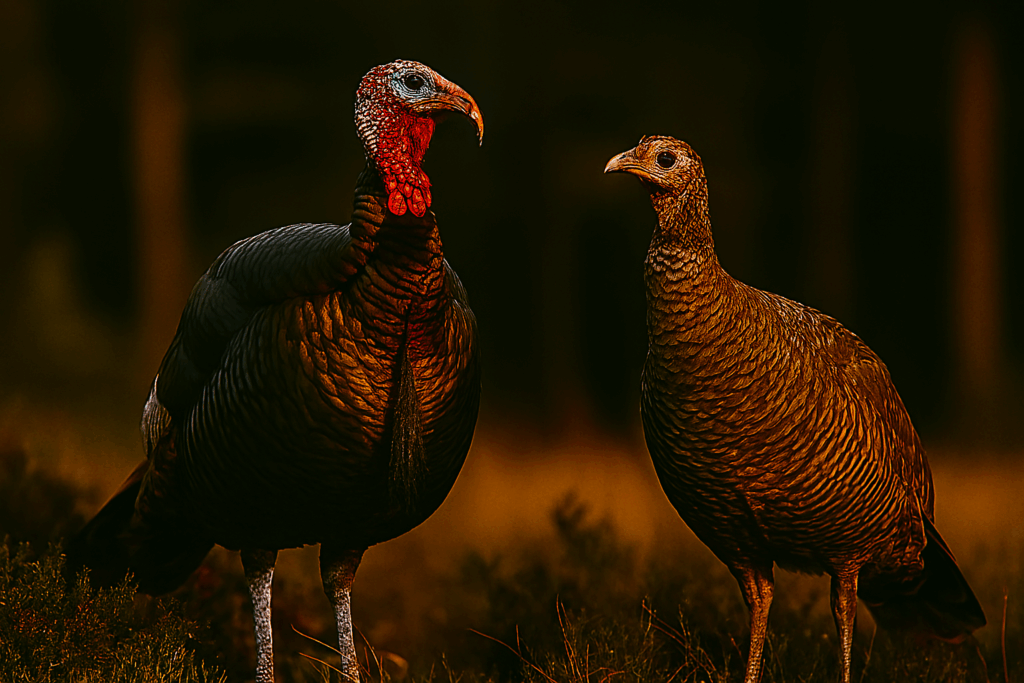

Merriam’s wild turkeys are the mountain athletes of the turkey world – built for high-altitude living and constant movement across rugged terrain. Adult gobblers weigh 18-30 pounds, with hens tipping the scales at 8-12 pounds. While similar in size to Eastern turkeys, Merriam’s are leaner and more athletic, adapted for life in thin air and steep country where survival demands mobility.

The distinguishing feature that sets Merriam’s apart from all other subspecies is their brilliant white tail feather tips – “about as white as white can get,” according to experienced hunters. These snow-white tips create a striking contrast against dark backgrounds and make strutting gobblers visible from incredible distances. The white markings extend to the lower back feathers and rump coverts, giving birds an almost luminescent white patch when viewed from behind.

The body plumage of Merriam’s turkeys appears black at a distance but reveals blue, purple, and bronze reflections in sunlight. They have more white and less black on their wings compared to Eastern turkeys, giving the folded wings a lighter appearance. Males display the typical turkey features – prominent snoods, caruncles, and wattles that turn bright red during excitement, along with the characteristic beard growing from the breast.

Merriam’s gobblers produce a distinctive gobble that hunters describe as weak, lazy, or wispy compared to the booming roars of Eastern turkeys. This high-pitched, yodel-like call carries well across mountain valleys but lacks the deep resonance of their eastern cousins. The unique sound perfectly matches their mountain environment, where echoes bounce off canyon walls and ridge faces for miles.

Their legs are long and powerful, built for walking incredible distances across varied terrain from rocky slopes to high meadows. These birds are marathon walkers, capable of covering 2-3 miles without stopping as they search for food and suitable habitat. Their feet are larger than other subspecies, providing better traction on steep, rocky surfaces.

The subspecies was named in 1900 to honor Clinton Hart Merriam, the first chief of the U.S. Biological Survey. Originally native only to ponderosa pine forests of Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado, successful transplant programs have established populations across 14 states throughout the Rocky Mountain region.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Merriam’s wild turkeys inhabit the ponderosa pine forests and high-elevation country of the American West, from the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast ranges. Their natural range originally included only Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado, but aggressive restoration programs have established thriving populations throughout Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Washington, Oregon, California, Nebraska, and South Dakota.

These birds are creatures of elevation, typically found between 3,500 and 10,000 feet above sea level. They prefer the transition zones where ponderosa pine forests meet oak brush, aspen groves, and mountain meadows. Unlike Eastern turkeys that demand dense cover, Merriam’s thrive in more open forest structure with scattered clearings and diverse vegetation types.

The key habitat components Merriam’s require include mature ponderosa pines for roosting, with birds selecting trees 15-30 inches in diameter on steep slopes and ridgetops. They need diverse food sources including pine nuts, acorns from Gambel’s oak, grass seeds, forbs, and insects found in meadows and forest openings. Water sources are critical, as these birds rarely travel far from reliable water in the arid West.

Seasonal movements are pronounced, with birds following elevation gradients as snow melts in spring and accumulates in fall. They winter at lower elevations in pinyon-juniper and oak brush zones, then move upslope as breeding season progresses. Some birds travel 40+ miles between seasonal ranges, following traditional corridors used for generations.

The rugged topography Merriam’s prefer creates unique hunting challenges. They select roosting sites on steep slopes and canyon rims that provide security but require extreme physical effort to access. Birds often roost in the same trees for weeks, then abandon the area entirely and move miles away. This mobility makes patterning Merriam’s nearly impossible compared to other subspecies.

Current populations are stable to increasing throughout most of their range, with approximately 334,000-344,000 birds across all states. Colorado alone supports birds across 19,000 square miles of suitable habitat, while Montana hosts approximately 120,000 Merriam’s. New Mexico has the highest concentration of any single state, with birds found in most mountain ranges statewide.

Behavior and Hunting Challenges

Hunting Merriam’s wild turkeys presents unique challenges that separate these birds from all other subspecies. The primary difficulty isn’t killing the turkey once you find it – it’s finding the damn thing in the first place. These birds are nomadic wanderers that never seem to stop moving, covering miles of rugged terrain daily as they search for food and suitable habitat.

The mobility of Merriam’s turkeys is legendary among western hunters. From the moment they fly down at dawn until they roost at sunset, these birds are constantly on the move. Unlike Eastern turkeys that might spend days in the same hollow, or Rio Grandes that follow predictable patterns, Merriam’s can roost in one canyon and feed five miles away in a completely different drainage. One hunter tracked a pair of toms that walked over two miles before he lost sight of them, and that was just during morning feeding.

This constant movement stems from the scattered nature of their food sources in mountain environments. Merriam’s must travel between pine nut concentrations, oak brush patches, meadows with insects, and water sources to meet their daily needs. The low productivity of high-elevation habitats forces birds to cover vast areas to find sufficient nutrition, especially during breeding season when energy demands peak.

Merriam’s turkeys exhibit different flocking behavior than other subspecies, staying in large groups longer during spring. While Eastern turkeys break up into breeding units early in the season, Merriam’s often maintain flocks of 10-20 birds well into April. This creates situations where hunters must deal with multiple sets of eyes and ears, making approaches extremely difficult.

The terrain these birds inhabit adds another layer of complexity to hunting them. Elevations from 5,000-9,000 feet challenge even well-conditioned hunters. Steep slopes, loose rock, deadfall timber, and unpredictable weather conditions make every hunt a physical test. Spring snowstorms can shut down hunting for days, while altitude sickness affects flatlanders unprepared for thin air.

Weather plays a huge role in Merriam’s behavior and hunter success. Late spring storms are common in mountain country, forcing birds to shelter in dense timber for days. High winds make calling difficult and reduce gobbling activity. Rapid temperature swings affect bird movement patterns, with cold snaps sending turkeys to lower elevations and warm spells drawing them upslope.

Unlike other subspecies that become call-shy under pressure, Merriam’s often respond aggressively to calling throughout the season. However, their response might involve moving toward the hunter but stopping 200-400 yards away and expecting the “hen” to come to them. This behavior creates frustrating situations where birds gobble enthusiastically but never offer shot opportunities.

Hunting Strategies and Techniques

Successfully hunting Merriam’s turkeys requires abandoning traditional sit-and-wait tactics in favor of aggressive, mobile strategies that match the birds’ nomadic lifestyle. These mountain gobblers demand hunters who can cover ground quickly, adapt to changing conditions, and maintain physical stamina throughout long days in challenging terrain.

The run-and-gun approach works exceptionally well for Merriam’s because these birds respond aggressively to calling and aren’t as pressure-sensitive as Eastern turkeys. Start each morning by covering ground quickly, stopping every quarter-mile to call and listen for responses. Use locator calls like owl hoots, crow calls, or even elk bugles to shock gobble distant birds. Once you locate a bird, don’t waste time setting up elaborate ambushes – get moving and close the distance rapidly.

Calling strategies for Merriam’s should be more aggressive than techniques used for other subspecies. These birds expect to hear loud, frequent vocalizations due to the windy, open nature of their habitat. Don’t be afraid to call every few minutes, using excited yelps, cuts, and clucks to maintain contact with moving birds. Box calls work excellent for long-distance locating, while diaphragm calls provide hands-free mobility when pursuing responsive gobblers.

The mobility factor cannot be overstated when hunting Merriam’s. Be prepared to hike 3-5 miles during a typical hunt, often covering 2,000+ feet of elevation gain in the process. Pack light but carry essentials including water, snacks, extra calls, and survival gear for emergencies. Quality boots with ankle support are mandatory – twisted ankles end more Merriam’s hunts than empty shotgun shells.

Elevation advantages work in your favor when hunting mountain turkeys. Position yourself on ridgetops or high benches where you can glass distant meadows and clearings for birds. Binoculars are essential equipment for spotting turkeys at distances exceeding half a mile. When you locate birds visually, plan your approach carefully to avoid skylining yourself on ridges where birds can spot movement from miles away.

All-day hunting produces excellent results with Merriam’s since these birds remain active throughout daylight hours. While most hunters quit by 10 AM, smart hunters continue pursuing birds through midday when competition decreases. Merriam’s often take midday shade breaks in dense timber, providing opportunities for patient hunters willing to wait them out.

Decoy strategies for Merriam’s require different thinking than other subspecies. The open country these birds inhabit allows them to spot decoys from incredible distances, but it also means they can approach from any direction. Position decoys in small clearings where approaching birds must come within range, and always have escape routes planned since mountain terrain can trap unwary hunters.

Weather awareness is critical for Merriam’s hunting success. Learn to read mountain weather patterns and adjust tactics accordingly. Hunt lower elevations during storms, focus on south-facing slopes that warm first, and be prepared for rapid weather changes that can turn pleasant mornings into survival situations. Spring snowstorms can dump 6+ inches overnight, making access roads impassable and forcing complete tactical changes.

Public Land Locations and Access

Merriam’s turkeys offer some of the best public land hunting opportunities of any game species in North America, with millions of acres of National Forest, Bureau of Land Management, and state lands providing access to quality habitat. The key to success lies in understanding which areas hold birds and being willing to work for access to less pressured locations.

Colorado ranks among the top states for public land Merriam’s hunting, with birds inhabiting approximately 19,000 square miles of suitable habitat. The San Juan National Forest, White River National Forest, and Pike National Forest offer extensive hunting opportunities. Garfield, Mesa, Delta, Archuleta, and Yuma counties produce the most turkeys annually. Colorado Parks and Wildlife describes turkey populations as doing well overall, with some local variations due to weather impacts.

Montana provides exceptional public land access for Merriam’s hunters, with approximately 120,000 birds distributed across the state. The transplant programs beginning in the 1950s have been incredibly successful, with birds now found in most suitable habitat statewide. Public access includes National Forest lands, state wildlife management areas, and walk-in hunting areas on private land enrolled in access programs. Block Management Areas provide additional opportunities throughout central and eastern Montana.

Wyoming consistently ranks as the top destination for traveling Merriam’s hunters, with excellent public land access and good bird populations. The Black Hills region provides some of the most consistent hunting in the state. Wyoming offers numerous Walk-In Areas – private ground under public hunting agreements – that often hold excellent turkey populations with reduced pressure. Properties in 14 counties provide this access and represent prime hunting locations.

New Mexico holds more Merriam’s turkeys than any other subspecies and offers good public land access throughout the state. The Sacramento Mountains in south-central New Mexico, Gila National Forest, and Zuni Mountains in Unit 10 provide excellent hunting opportunities. Most mountain ranges support huntable turkey populations, and hunter pressure remains relatively low compared to other western states.

Idaho offers over-the-counter turkey tags for nonresidents at reasonable prices, with a two-bird bag limit. While not all game management units are open to turkey hunting, those that are provide good access to quality birds. Season dates run from mid-April through late May, providing flexible hunting opportunities.

Arizona requires draw permits for most turkey hunting but offers some over-the-counter opportunities for archery hunters and in select units. The state supports approximately 25,000 Merriam’s turkeys concentrated in northern and eastern regions. Despite limited tags, Arizona provides excellent hunting for those who draw permits.

The key to success on public land is accessing areas that receive minimal hunting pressure. Focus on locations requiring 2+ miles of hiking from roads or parking areas. Most hunters won’t venture beyond half a mile from vehicle access, leaving vast areas of quality habitat available to those willing to work for it. Use topographic maps and satellite imagery to identify remote pockets of suitable habitat that others overlook.

Early season hunting provides the best opportunities before birds become educated and dispersed by hunting pressure. Plan hunts during weekdays when recreational users and other hunters are reduced. Scout potential areas during pre-season trips to identify roost sites, feeding areas, and access routes.

Season Information and Regulations

Merriam’s turkey seasons across the western states generally run from mid-April through May, coinciding with peak breeding activity at high elevations. However, regulations vary significantly between states, with some requiring draw permits while others offer over-the-counter opportunities.

Colorado offers over-the-counter spring turkey tags with season dates from April 12 through May 31. Bag limits allow one turkey with either sex birds legal during fall seasons and bearded birds only during spring. Hunting hours extend from one-half hour before sunrise to sunset. Some units require limited draw permits, particularly those with Rio Grande turkeys on the eastern plains.

Montana requires licenses for turkey hunting with general tags valid statewide for male turkeys during spring seasons. Some areas use limited draw permits to control harvest, while others remain over-the-counter. Bag limits typically allow one bird per license, with additional regional licenses available in some areas. Montana’s season structure accommodates both residents and nonresidents but check current regulations for specific unit requirements.

Wyoming historically provides good over-the-counter opportunities but has been transitioning some areas to limited draw systems due to increasing hunter interest. Season dates generally run from April through May depending on unit and elevation. Bag limits allow one bearded bird per tag, with hunters able to purchase additional licenses in some areas.

New Mexico offers both over-the-counter and limited draw hunts depending on unit. OTC seasons typically run from April 15 through May 10 for most units. Limited draw areas often have longer seasons and may allow additional harvest opportunities. Nonresident hunters pay higher fees but generally have good access to quality hunting areas.

Idaho provides over-the-counter opportunities for both residents and nonresidents, with seasons running April 15 through May 25 in designated units. Bag limits allow two bearded birds per license, making Idaho attractive for traveling hunters. License costs are reasonable, with nonresident tags around $88.

Arizona operates primarily on a draw system for turkey hunting, with applications due in October for the following spring. However, some units offer over-the-counter archery opportunities from May 9-22. Bag limits are restricted to one turkey per calendar year. Despite limited access, Arizona provides excellent hunting for those who draw tags.

Washington allows three turkeys per season with specific restrictions by area. Eastern Washington permits two birds except Spokane County allows three, while Western Washington allows one bird. Klickitat County provides additional opportunities with a two-bird limit. Season dates run from April 15 through May 31 for general seasons.

Legal hunting hours across most states begin one-half hour before sunrise and continue to sunset. Some states restrict spring hunting to morning-only hours during peak breeding periods to reduce hunter conflicts and improve safety. Weapon restrictions typically allow shotguns, muzzleloaders, and archery equipment, with most states prohibiting rifles during spring seasons.

Hunter education requirements are mandatory in most states, with some requiring specialized turkey hunting courses. License requirements include basic hunting licenses plus turkey stamps or permits. Check-in requirements vary by state, with some requiring harvest reporting within 24-72 hours.

Trophy Considerations and Record Keeping

Merriam’s wild turkeys produce impressive trophy birds despite being slightly smaller than Eastern turkeys in terms of beard length and spur development. The distinctive white-tipped tail feathers make Merriam’s the most visually striking subspecies, and their mountain lifestyle creates birds with unique character and memorable hunting experiences.

Adult gobblers typically weigh 18-30 pounds, with exceptional birds reaching the low 30-pound range. The heaviest Merriam’s entered in National Wild Turkey Federation records weighed 31.5 pounds. While not as heavy as the largest Eastern turkeys, Merriam’s gobblers are athletic, well-proportioned birds that represent the epitome of mountain game.

Beard length averages 8-10 inches on mature gobblers, with exceptional birds sporting beards exceeding 11 inches. While generally shorter than Eastern turkey beards, Merriam’s beards are often fuller and more dense due to the harsh mountain environment. The contrast between dark beards and white tail tips creates a striking visual that makes these birds unmistakable in the field.

Spur development varies significantly based on age and habitat conditions, with mature toms developing sharp, curved spurs 1-2 inches in length. Mountain living creates dense, hard spurs due to the rocky terrain these birds traverse daily. Exceptional old gobblers may have spurs approaching 2.5 inches, though such birds are rare.

The National Wild Turkey Federation maintains official scoring records using a formula that combines beard length, spur measurements, and body weight. The minimum score for NWTF record book entry helps hunters understand what constitutes a truly exceptional bird worthy of official recognition.

For hunters pursuing a turkey Grand Slam, Merriam’s typically represent the most accessible subspecies due to extensive public land access and reasonable license costs. Many hunters complete their Grand Slam with Merriam’s birds taken on challenging mountain hunts that provide lasting memories beyond simple trophy measurements.

The visual impact of a strutting Merriam’s gobbler with fanned white tail tips against a backdrop of ponderosa pines and mountain peaks creates images that remain with hunters for life. These birds represent the wilderness character of the American West and provide trophy experiences that transcend simple measurements.

Quality taxidermy work becomes especially important for Merriam’s due to their distinctive white markings that must be preserved properly. Photograph birds immediately after harvest with measurements visible for documentation. The white tail tips can become soiled during field handling, so take care to preserve the pristine appearance that makes these birds so distinctive.

Field care should focus on protecting the white plumage and preventing blood stains that detract from the bird’s appearance. Cool birds quickly in mountain environments where temperatures can fluctuate rapidly. Proper care ensures the distinctive white markings remain pristine for taxidermy work.

Conservation and Population Status

Merriam’s wild turkeys represent one of the most successful transplant stories in wildlife management history, expanding from a limited native range to thriving populations across 14 western states through aggressive restoration programs. Current populations are stable to increasing throughout most of their range, though they face emerging challenges from climate change and catastrophic wildfire.

Historical populations were restricted to ponderosa pine forests of Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado, with Merriam’s relatively isolated from other turkey subspecies. The subspecies did not exist in Montana, Wyoming, or most of its current range prior to 1950. Restoration efforts began in earnest during the 1950s with trap-and-transfer programs moving wild birds to suitable unoccupied habitat.

Montana’s restoration program exemplifies the success possible with proper management. Starting with 13 birds imported from Wyoming in 1954, followed by additional releases totaling 57 birds through 1957, the state now supports approximately 120,000 Merriam’s turkeys. All subsequent releases used offspring from these initial transplants, demonstrating how small founder populations can create thriving subspecies with proper habitat.

Current population estimates across all states range from 334,000-344,000 birds, with populations stable to increasing in most areas. Colorado supports birds across 19,000 square miles of habitat, while states like Wyoming and Montana have seen populations exceed social carrying capacity in some areas.

The success of Merriam’s restoration stems from several factors including extensive public land holdings with suitable habitat, careful initial harvest management that allowed populations to establish, and the subspecies’ adaptability to various elevation zones and forest types. Western states’ use of limited entry permits inherently controls hunting pressure and ensures sustainable harvest levels.

However, Merriam’s populations face emerging challenges that could affect long-term viability. Catastrophic wildfire represents the greatest threat, with increasingly intense fires destroying thousands of acres of turkey habitat annually. While turkeys tolerate moderate natural fire that creates beneficial edge habitat, stand-replacing fires eliminate roosting trees and food sources for decades.

Drought conditions exacerbate wildfire risks while reducing habitat quality and reproductive success. Extended dry periods stress ponderosa pine ecosystems and reduce insect populations critical for poult survival. Climate change threatens to intensify both drought cycles and wildfire frequency across the West.

Cold, wet weather during peak hatching periods causes significant poult mortality when young birds lack sufficient feathers for thermoregulation. Spring weather patterns in mountain environments can shift rapidly, with late snowstorms and cold rain creating hypothermic conditions for newly hatched poults.

Conservation efforts focus on landscape-level forest management including prescribed burning to reduce catastrophic fire risk, forest thinning to improve habitat structure, and riparian area protection to maintain water sources. The National Wild Turkey Federation works with land management agencies to implement science-based habitat improvements across millions of acres of public land.

Partnerships between government agencies, private landowners, and conservation organizations remain essential for addressing emerging threats and maintaining healthy populations. Hunter-generated revenue through license sales continues to fund research and management programs necessary for long-term conservation success.

Tips for First-Time Hunters

Hunting Merriam’s turkeys for the first time is like entering a whole different world of turkey hunting – one where the birds never stop moving, the country will test every muscle in your body, and success requires more mountain climbing than turkey calling. These birds will humble experienced Eastern turkey hunters who think they know what turkey hunting is all about.

Accept that you’re going to get your butt kicked physically before you ever see your first bird. Merriam’s country doesn’t care about your comfort level or fitness – it’s steep, rocky, high-altitude terrain that will leave flatlanders gasping for air. Start conditioning months before your hunt with hiking, stair climbing, and cardio work that prepares you for extended efforts at 7,000+ feet elevation. Pack light but carry water and snacks because you’ll be covering serious ground.

Learn to hunt with your eyes as much as your ears. Unlike Eastern turkeys hidden in thick timber, Merriam’s inhabit open country where you can spot birds from miles away with quality binoculars. Spend time glassing meadows, clearings, and distant ridges before making moves. Pattern recognition becomes crucial – learn to identify turkey movement and posture at distances where you can’t hear calling.

Aggressive calling works better with Merriam’s than any other subspecies, so abandon the subtle techniques that work back East. These birds expect loud, frequent vocalizations due to windy mountain conditions and vast distances. Don’t worry about over-calling or making birds call-shy – worry about not being heard over wind and terrain. Box calls excel for long-distance locating while mouth calls provide mobility when pursuing birds.

Mobility is everything when hunting Merriam’s. Plan to hike 3-5 miles during typical hunts, often involving serious elevation changes. Don’t waste time setting up elaborate blinds or decoy spreads that work for other subspecies – these birds are gone before you finish arranging your setup. Get light, travel fast, and be ready to change locations quickly when birds move.

Hunt all day because Merriam’s remain active throughout daylight hours, not just during traditional morning periods. While most hunters quit by mid-morning, smart hunters continue pursuing birds when competition drops off. Midday shade-ups in timber can provide excellent opportunities for patient hunters.

Weather becomes a major factor in mountain turkey hunting. Learn to read weather patterns and adjust tactics accordingly. Hunt lower elevations during storms, focus on south-facing slopes that warm first, and always carry emergency gear because mountain weather changes rapidly. Spring snowstorms can shut down hunting for days, so build flexibility into your plans.

Prepare for different gobbling behavior than other subspecies. Merriam’s produce weak, wispy gobbles that sound lazy compared to Eastern turkey roars. Don’t expect the booming, thunderous gobbles you hear in turkey hunting videos – listen for high-pitched, yodel-like calls that carry differently across mountain terrain. Learn to interpret these subtle vocalizations to locate birds effectively.

Safety considerations become critical in mountain environments. Always tell someone your hunting plans and expected return time. Carry emergency gear including GPS devices, first aid supplies, and survival equipment. Mountain terrain can trap unwary hunters when weather deteriorates, turning routine hunts into survival situations. Know your physical limits and don’t exceed them trying to pursue birds beyond your capabilities.

Study topographic maps and satellite imagery to understand the terrain before arriving. Identify potential access routes, escape routes, and areas likely to hold birds. Use modern technology including mapping apps to navigate safely, but don’t depend entirely on electronics in remote areas. Learn basic navigation skills and carry backup compass and paper maps.

Most importantly, adjust your expectations about shot opportunities and success rates. Merriam’s hunting involves more hiking than shooting, more glassing than calling, and more endurance than technique. The birds you do encounter will likely be at longer ranges than Eastern turkey hunters expect. Practice shooting from various positions at realistic distances for mountain hunting scenarios. Success comes to hunters who embrace the physical challenges and scenic beauty of mountain turkey hunting rather than those focused solely on filling tags.